The Hunters in the Snow

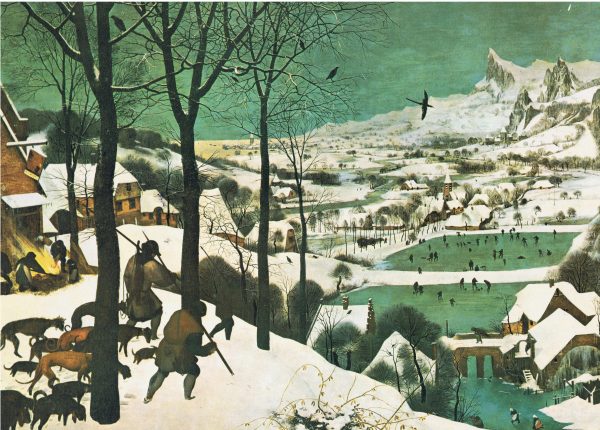

Pieter Bruegel painted this in 1565, in oil on panel, as one of a series of six works (five of which survive), commissioned by an Antwerp citizen, Niclaes Jonghelinck. Measuring 117×162 cm (46×63¾in), it is currently in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Known as The Labours Of The Months, the series was probably the first full-scale celebrations in Western art of landscape for its own sake, with human business inextricably involved with nature, with the hills & plains, water & air, & with the changing seasons.

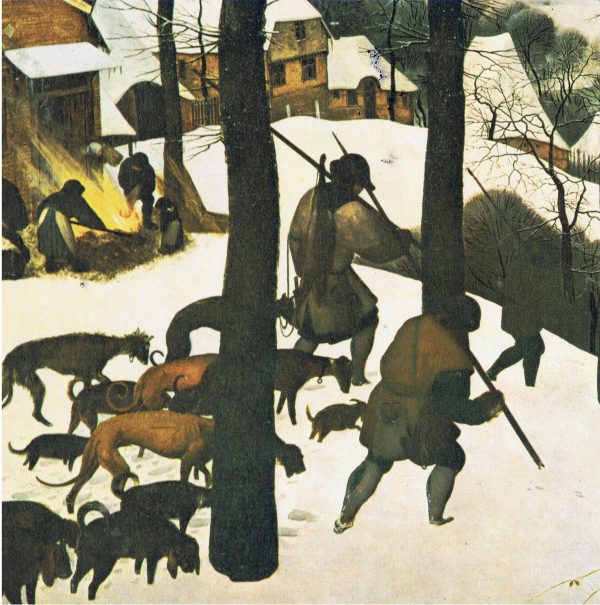

This painting, combining the school of monumentalisation with an extreme simplification of figures, depicts a cold, overcast winter’s day as a group of hunters are returning from an unsuccessful outing: they seem weary & discouraged – even the dogs look miserable. One hunter carries a dead fox over his shoulder: it’s not much of a bag!

A close-up of the Huntsmen

There and Back Again

As they trudge home, although some villagers are still working, others are having fun on the ice: skating, curling, & playing ice-hockey. Although they are only silhouettes, the holiday atmosphere comes across so that you can almost hear their shouts of joy.

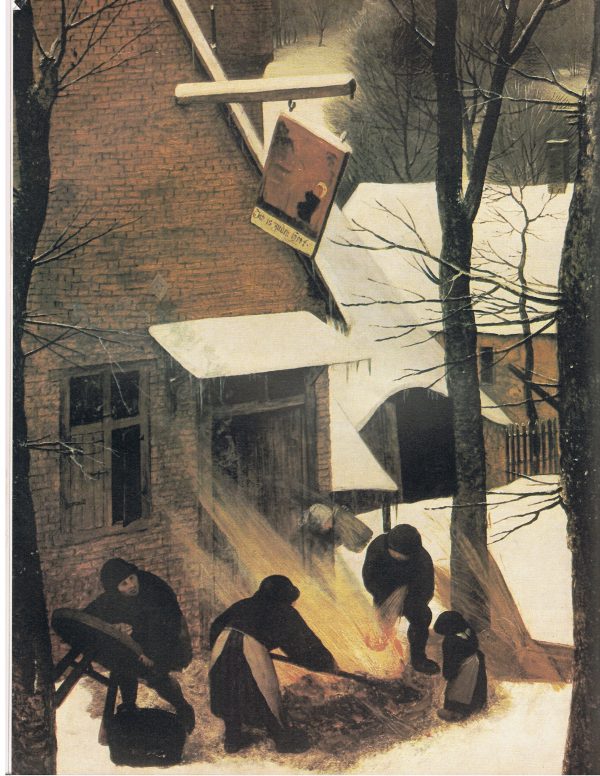

Outside the inn with its broken sign, as if to comfort the hunstmen for their lack of success, people are singeing a slaughtered pig: a man is bringing over the pig stool ready to butcher the animal, while a little girl, dressed just like her mother, watches & learns.

A close-up of the Inn

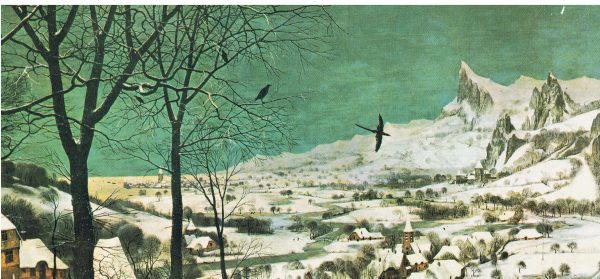

The landscape itself is a flat-bottomed valley, looking both fertile & prosperous, with a river meandering through it & with jagged peaks visible in the distance. This is a convention much used by Flanders artists, inhabitants of one of the flattest landscapes in Europe: because of their native plains they were obsessed by mountains. Bruegel had drawn the Alps as he crossed to & from Italy, & for ever afterwards he remembered their haunting desolation & grandeur.

Structure

A close-up of the valley

Cultural Background

This work was created against the background of the Revolt of the Netherlands (1566, or 1568–1609), the partially successful revolt of the Protestant Seventeen Provinces of the defunct Duchy of Burgundy against the militant religious policies of Roman Catholicism pressed by both Charles V and his son Philip II. The religious clash of cultures built up gradually but inexorably into outbursts of violence against the perceived repression of the Spanish Crown, marking the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War and leading to the formation of the independent Dutch Republic, of which the first leader was William of Orange. (However, in the shape of the church towers, echoed by the crags, we may see a precursor of Wordsworth’s religious ecstasy on his communion with nature (1790): He holds with God himself communion high There where the peal of swelling torrents fills The sky-roofed temple of eternal hills)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Born in Breda, in the Duchy of Brabant, which is now part of the Netherlands but was then part of Flanders, Bruegel was accepted as a master in the Antwerp painters’ guild in 1551, after his apprenticeship to Pieter Coecke van Aelst, a leading Antwerp artist who had settled in Brussels. Bruegel travelled to Italy in 1551 or ’52, producing a number of works – mainly landscapes – while there. Returning home in 1553, he settled in Antwerp but ten years later married van Aelst’s daughter, Mayken, and moved permanently to Brussels.

The Hunters in the Snow

Bruegel’s paintings, including his landscapes and scenes of peasant life, stress the absurd and the vulgar, yet are full of zest and fine detail. They also expose human weaknesses and follies – for which he was sometimes called the Peasant Bruegel. But it was in nature that he found his greatest inspiration – his mountain landscapes have few parallels in European art.

To Conclude

Bruegel died on September 9th, 1569 & was buried in Notre-Dame de la Chapelle in Brussels.

I love this painting because of the tenderness & sympathy with which Bruegel shows not just a scene, but a whole way of life – you can taste the tang of frost in the air, & hear the cries of joy from the people playing on the ice. It gives us a window into the simple pleasures country people found in their lives at that time, despite the harshness of the weather, the difficulties of finding enough to eat, & the arduous daily grind.